Sathish Sowmya* and LAU Siu-Kit, Eddie

Department of Architecture, College of Design and Engineering (CDE), NUS

Sub-Theme

Others – Building Spatial Relationships: Between Educator and the Physical Learning Environment

Secondary Sub-theme – Building Learning Relationships (Through Space)

Keywords

Spatial flexibility, educator agency, classroom activation, learning environment, relational pedagogy

Category

Paper Presentation

Introduction

As institutions invest in flexible learning spaces to meet 21st-century educational needs, the emphasis has largely remained on physical design and student outcomes. What remains under-theorised is the role of the physical learning environment in supporting not just instructional strategies, but the relational dimensions of teaching and learning. This paper argues that flexible affordances within classrooms is not merely an infrastructural feature, but a relational practice enacted by educators to foster trust, connection, and co-agency.

The guiding pedagogical orientation of this paper is the concept of relational pedagogy, which places human connection at the center of educational practice. Rather than viewing teaching as the transmission of knowledge, relational pedagogy emphasises care, responsiveness, and mutual respect as the foundation for co-constructing meaning within both interpersonal and environmental contexts (Bingham & Sidorkin, 2004; Noddings, 2012).

Classrooms, from this perspective, are not inherently relational; rather, they become sites of relational pedagogy when their spatial attributes are activated in response to pedagogical intent and learner needs. This view builds on the premise that space is not a passive backdrop to teaching, but an agentive component in learning, one that shapes and is shaped by educator and student interactions (Boys, 2010; Brooks, 2011; Byers et al., 2014; Fenwick et al., 2011; Mulcahy, 2012). This understanding is also informed by three intersecting theoretical frameworks:

- Constructivist Learning Theory (Piaget, 1964; Vygotsky, 1978) which emphasises learner-driven meaning-making through social interaction, highlighting the need for spatial configurations that support collaboration and shared inquiry.

- Socio-Material Theory (Fenwick et al., 2011), which conceptualises classrooms as assemblages where material elements, including space, co-produce participation, positioning educators as spatial agents.

- Cognitive Flexibility Theory (Spiro et al., 1992), which underscores the value of adaptable environments in supporting flexible thinking and diverse learning pathways.

Informed by these frameworks, this study investigates the question:

How do the spatial attributes of flexible classrooms influence relational pedagogy?

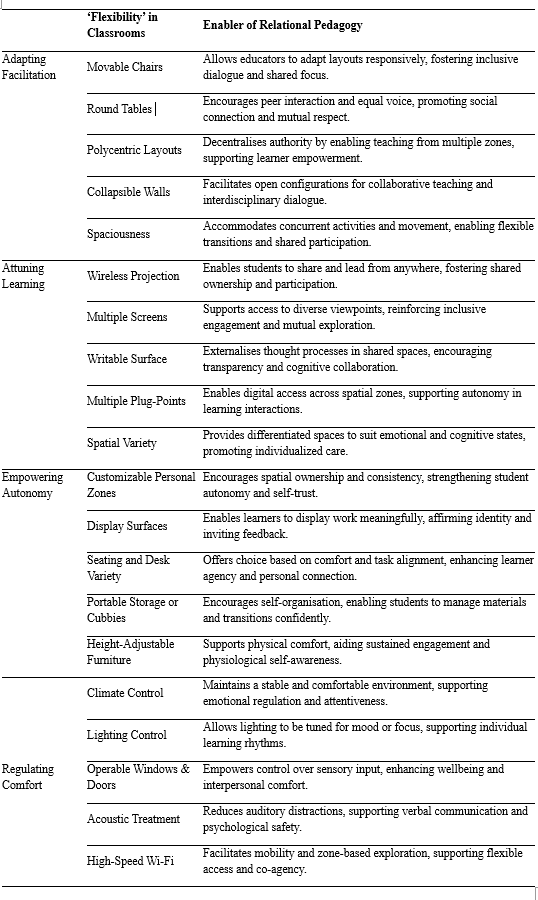

To address this, a systematic literature review was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, drawing from 118 peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2024 across education, architecture, and learning sciences. Data were analysed using thematic synthesis informed by grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006). Open and axial coding techniques were employed to identify spatial functions and educator-led practices, leading to the identification of four core strategies through which educators relationally engage with learning environments:

- Adapting Space for Dynamic Facilitation: Educators reconfigure layouts, furniture, zones, and circulation, to respond to group dynamics and lesson goals. This flexibility affirms student voice and supports co-participation.

- Attuning Space to Learner Preferences: Through deliberate adjustments to lighting, acoustics, or layout density, educators create emotionally supportive environments that enhance psychological safety and relational trust.

- Empowering Choice through Spatial Autonomy: By offering students control over where and how they work, educators promote agency and differentiated engagement, positioning space as an expression of trust and respect.

- Regulating Climate for Relational Comfort: Educators manage environmental factors such as airflow, lighting, and digital access to sustain attention, calm, and wellbeing, recognising the embodied nature of learning.

Flexible spatial features supporting relational pedagogy

.

To illustrate these strategies in practice, Table 1 synthesises the identified flexible spatial attributes and maps them to their educator-mediated relational functions. Rather than viewing flexibility as a fixed set of design affordances, the findings reframe it as a series of context-sensitive strategies enacted by educators to shape learning relationships. This perspective introduces a conceptual shift from evaluating physical space in isolation to understanding it through the adaptive pedagogical practices that activate its relational potential. In doing so, the review contributes a practitioner-oriented lens that positions spatial agency as integral to pedagogical work, offering a framework for designing and evaluating flexible classrooms based on their enacted use and relational outcomes.

References

Bingham, C., & Sidorkin, A. (2004). No Education without Relation.

Boys, J. (2010). Towards creative learning spaces. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203835890

Brooks, D. C. (2011). Space matters: The impact of formal learning environments on student learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(5), 719-726. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01098.x

Byers, T., Imms, W., & Hartnell-Young, E. (2014). Making the case for space: The effect of learning spaces on teaching and learning. Curriculum and Teaching, 29(1), 5-9. https://doi.org/10.7459/ct/29.1.02

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. In (Vol. 1).

Fenwick, T. J., Edwards, R. J., & Sawchuk, P. H. (2011). Emerging Approaches to Educational Research: Tracing the Socio-Material. Routledge.

Mulcahy, D. (2012). Thinking teacher professional learning performatively: A socio-material account. Journal of Education and Work, 25(1), 121-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.644910

Noddings, N. (2012). The caring relation in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 38(6), 771-781. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.745047

Piaget, J. (1964). Cognitive development in children: Development and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2, 176-186. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660020306

Spiro, R. J., Feltovich, P. J., Jacobson, M. J., & Coulson, R. L. (1992). Cognitive flexibility, constructivism, and hypertext: Random access instruction for advanced knowledge acquisition in ill-structured domains. Educational Technology, 31, 24–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44427517

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (Vol. 86). Harvard University Press.