Sub-Theme

Building Technological and Community Relationships

Keywords

Interdisciplinary education, soundwalk, making connections

Category

Paper Presentation

Background of the Course

With the focus of building an interdisciplinary community and empowering learners to connect across disciplinary boundaries, the NUS College’s “Making Connections” courses aim to help students apply their foundational competencies (such as quantitative reasoning, thinking with writing, and computational thinking) through small-class experiential learning that integrates theory, practice, and engagement with the real-world environment. Offered under the “Making Connections” courses, NST2055 “Comprehending Sound Around Us” invites students from different disciplines to explore the multifaceted role of sound in shaping our perception of the environment around us. The ethos of Making Connections is realised through a syllabus that bridges physics, cognitive science and design, where sound is not only described as a scientific phenomenon but also as a cultural artifact. As such, this course fosters ecological sensibilities and strengthens technological and community relationships between the learners and their lived environment.

Inspiring the Educator: Building Relationships Between Abstract Physical Concepts and the Real-World During Content Building

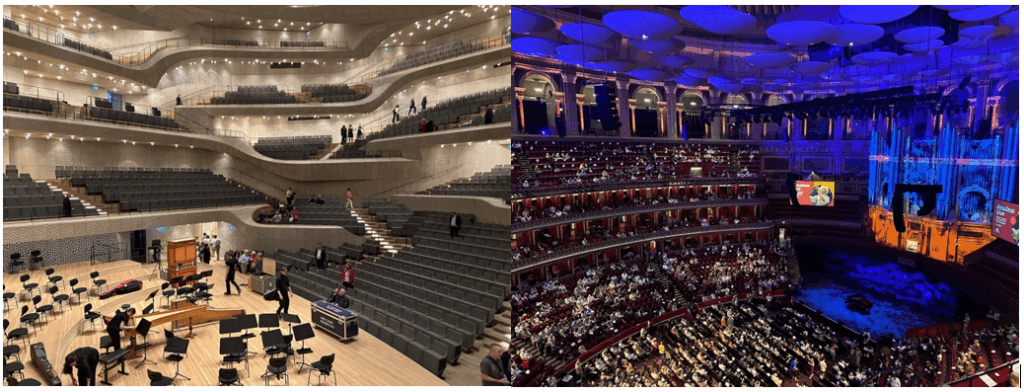

Given that a key motivation for the design of the course is for students to have a heightened awareness of the production and reception of sound around them, the journey started with myself exercising the same heightened awareness, looking for places where sound is purposefully created and perceived—performance halls are one such example. Having a dual identity as a performer, I have frequent access to local concert halls to acquire insights of the inner workings of the acoustical properties of such halls. Even as I travel, I would visit different halls and collect photo and video artefacts of these halls (similar to the practice of soundwalks [Adams, et al., 2008]), and these photo and video artefacts then serve as examples in class to discuss the various sound treatment strategies in these purpose-built halls (Figure 1). Such is an example of how an educator could interact with their environment to look for inspiration in order to inform their teaching: in this case, the real-world examples that could relate the abstract physics concepts of sound absorption, diffraction, reflection, and diffusion to actual designs that could be seen. Furthermore, this could spur further discussions on how designers could design such spaces that not only tackle the functional needs of sound projection, but also how both aesthetics and space perception could be concurrently taken into consideration.

Figure 1. Some photo artefacts of the halls that I visited: (Left) Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg and (right) Royal Albert Hall in London.

.

Helping Learners Build Relationship Between Concepts and the Real World

Similar inspirations could be found in the environment that the students are situated in. After sharing the stories with the students on how I embarked on a journey to explore the sonic properties of different concert halls and elaborated on some of my findings, I got the students to consider how such acoustic designs are used in the classroom that they were in. With that, students not only had to relate to my sharing and the theoretical concepts that were covered in class, but they also had to think through the differences in the use cases between a space for performing arts and for lessons (Figure 2).

To drive home the point that there are many sound design considerations (or sometimes the lack thereof) in the spaces around us, the course concluded with a walking tour around the campus. To increase the interactivity of the walking tour, I invited students to bring their musical instruments to play at the different locations during the walk. Students were then invited to observe the differences in the music playing while at different locations in both the capacity of the performer and audience. Students were first brought to an enclosed stairwell where the hard surfaces result in an extreme long reverberation time, then a corridor with one side open, a drop-off point with an extremely high ceiling, and finally a performance hall purpose built for performing arts. By comparing the acoustics at different locations, students could appreciate in real-time how sound changes from listeners’ point of view (and equally interesting, how the location would affect how the players play).

Figure 2. Students exploring their perception of sound in a performance within NUS. A student brought an oboe and played it in different positions within the hall. The rest of the class started walking around to see if they could tell any differences in the sound quality.

.

As a concluding remark, given that students taking this course are from different academic backgrounds, inspiring students through the heightening of their senses and awareness becomes a useful mechanism for them to appreciate the interdisciplinarity and symbiosis of the different fields in describing sound. As such, this presentation seeks to elaborate how this may be done.

.

References

Adams, M. D., Bruce, N. S., Davies, W. J., Cain, R., Jennings, P., Carlyle, A., Cusack, P., Hume, K., & Plack, C. (2008). Soundwalking as a methodology for understanding soundscapes. Proceedings of the Institute of Acoustics. 30. 552-558. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286282168_Soundwalking_as_a_methodology_for_understanding_soundscapes_Institute_of_Acoustics_IOA