Samuel LOH Junhan*, Eunice S. Q. NG, and LIM Cheng Puay

Ridge View Residential College (RVRC), National University of Singapore (NUS)

Sub-Theme

Building Learning Relationships

Keywords

Peer learning, outdoor education, experiential learning, learning models, sustainability

Category

Lightning Talks

Effective sustainability education relies on participatory approaches that foster collaborative learning relationships between educators and learners (Mulà et al., 2017). Peer-to-peer pedagogical strategies, as a form of such engagement, enhances student relationships with other students and educators, fosters a sense of community, and create more relaxed learning environments (Asikainen et al., 2021, Buraphadeja & Kumnuanta, 2011; Deakin et al., 2012). Hence, integrating peer teaching alongside traditional educator-led sustainability programmes can enhance student learning outcomes and deepen their appreciation of sustainability (Tullis & Goldstone, 2020).

To this end, we incorporated peer teaching into the RV Intertidal Walk and Clean (ITWC) at Ridge View Residential College (RVRC). ITWC aims to foster a deeper appreciation among undergraduate students for Singapore’s coastal environments through coastal cleanups and guided intertidal walks. Traditionally, such College-led sustainability programmes rely on expert educators to deliver content on marine biodiversity, given the specialised knowledge required.

By introducing a peer guide to work alongside the expert guide, we aimed to explore:

- How does the involvement of a peer educator shape sustainability education outcomes?

- How does peer teaching impact the peer educator?

Methodology

Four ITWC trips were organised across Academic Year 2024/25 for 52 students within Singapore. Each trip was led by an expert nature guide and a peer guide. Participants completed a post-trip feedback form and a short reflection while the peer guide documented his reflections.

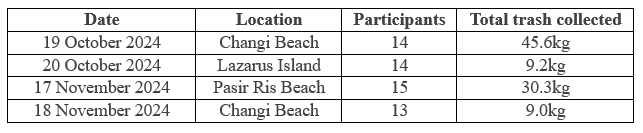

ITWC trips across Academic Year 2024/25

.

.

Results

1. Peer versus expert educator

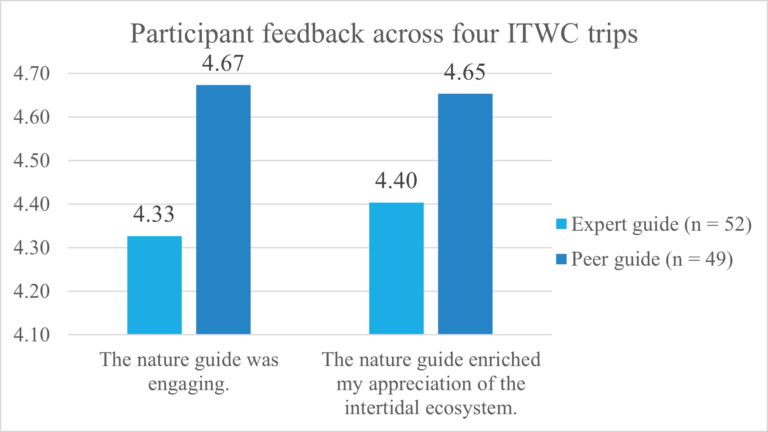

Figure 2 indicates that participants generally found the peer guide more engaging than the expert guide, with the difference in scores being statistically significant (p=0.001) with a one-tailed test. In addition, participants felt that the peer guide better enriched their appreciation of the intertidal ecosystem than the expert guide (p 0.002). Having a peer guide encouraged greater self-directed learning from the participants, as the peer guide’s “presence made the session feel more like an engaging sharing experience” and they “felt more comfortable asking questions, which deepened my understanding and encouraged open discussions”.

Qualitatively, a participant shared that the “a peer nature guide felt more relatable” while “a professional nature guide… could give us… detailed explanations of certain issues that our peer guide might not be able to give”, creating “a balance where (peer guide)’s approachable style was complemented by (expert guide)’s expertise”. Collectively, these indicate that having a peer guide enabled effective mediation of information between the expert guide and the participants, aligning with Bester et al. (2017)’s conclusion that peer teachers are a valuable supplement to the educator, but should not be seen as a replacement.

.

2. Impact on peer educator

In line with Asikainen et al. (2021), the peer teaching experience positively benefitted the peer guide’s social integration and sense of community. In his post-trip reflections, the peer guide reflected on how peer teaching allowed him to “contribute back to the College” and “(help) others experience the fun and joy I (the peer guide) find when interacting with nature”. While the peer guide was accustomed to leading nature activities for children and teenagers, guiding his peers was a new challenge. He noted that this role enabled him to “tackle more advanced topics”, such as “the experience and exploration aspects which are more intangible in nature”. As Deakin et al. (2012) highlight, peer teaching not only enhances the learners’ experience but also enriches the peer guide’s development in the topic.

Conclusion

This study highlights the impact that peer learning has on learners and peer educators, including increased engagement, social integration, and personal development. Within the contexts of educational institutions, existing sustainability education programmes can leverage the strengths of peer and expert-led teaching to enhance learning experience and outcomes without compromising the rigour of learning.

References

Asikainen, H., Blomster, J., Cornér, T., & Pietikäinen, J. (2021). Supporting student integration by implementing peer teaching into environmental studies. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(2), 162-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1744541

Bester, L., Muller, G., Munge, B., Morse, M., & Meyers, N. (2017). Those who teach learn: Near-peer teaching as outdoor environmental education curriculum and pedagogy. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 20, 35-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03401001

Buraphadeja, V., & Kumnuanta, J. (2011). Enhancing the sense of community and learning experience using self-paced instruction and peer tutoring in a computer-laboratory course. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(8). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.897

Deakin, H., Wakefield, K., & Gregorius, S. (2012). An exploration of peer-to-peer teaching and learning at postgraduate level: The experience of two student-led NVivo workshops. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 36(4), 603-612. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2012.692074

Mulà, I., Tilbury, D., Ryan, A., Mader, M., Dlouhá, J., Mader, C., Benayas, J., Dlouhý, J., & Alba, D. (2017). Catalysing change in higher education for sustainable development: A review of professional development initiatives for university educators. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 18(5), 798-820. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-03-2017-0043

Tullis, J. G., & Goldstone, R. L. (2020). Why does peer instruction benefit student learning? Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 5, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-020-00218-5