Lisa LIM Yu Qi*, Eunice S. Q. NG, and LIM Cheng Puay

Ridge View Residential College (RVRC), National University of Singapore (NUS)

Sub-Theme

Building Professional Relationships

Keywords

Teaching assistantship, sustainability education, experiential learning, peer learning

Category

Lightning Talks

Undergraduate teaching assistants (UTAs) are increasingly employed in higher education to support instructional needs, especially in active learning and introductory courses (Felege et al., 2022). While research has established the benefit of UTAs on student learning and their own professional development (Philipp et al., 2016), integrating UTAs effectively into teaching teams remains a complex and non-linear process. Drawing on Lave and Wenger (1991)’s model of legitimate peripheral participation, progressively involving UTAs in central teaching practices is important for nurturing their growth as emerging educators and enhancing the teaching team’s effectiveness.

Offered at Ridge View Residential College (RVRC), RVC2000 “Culture and Sustainability in Southeast Asia” explores the relevance of culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development through seminars and a 10-day overseas study trip to East or West Malaysia. Given the West Malaysia cohort size of 32 students, a UTA who completed the course was hired to support the two lecturers who have co-taught together. Integrating the new UTA into the teaching team was particularly important as overseas study trips entail more dynamic learning environments compared to traditional classroom-based seminars.

Pre-Trip Seminars

The lecturers initially assigned the UTA peripheral tasks to assist in the seminars. This included assisting in class discussions and sharing of insights. The team also planned for the UTA to independently facilitate a class discussion, providing her with adequate time to prepare ahead. These were structured learning sessions that the UTA was familiar with and had prior experience as a previous student in the course.

.

Overseas Study Trip

The shift from classroom learning to context immersion during the study trip expanded the educators’ role to include event planning, crisis response, and real-time engagement. The UTA felt that she “occupied an intersecting space between educator and student, where I straddled the responsibilities of leadership while still navigating my own learning curve”. This learning environment is conceptualised by Hogarth et al. (2015) as wicked, in contrast to kind learning environments where rules are clear, feedback is immediate, and outcomes are predictable.

.

Initially, the UTA lacked confidence in leading due to her self-identification as a ‘student’. Through intentional mentoring, the lecturers developed their rapport with the UTA, tailored tasks to her growth, and fostered her sense of belonging—key to her evolving self-conception as an ‘educator’. Guided by Lave and Wenger (1991)’s model of legitimate peripheral participation, the UTA gradually assumed a more central teaching role. This mentoring relationship not only empowered the UTA but also prompted the lecturers to refine scaffolding strategies for teaching in unstructured environments, driving the team’s overall growth.

.

Impact on Student Learning

The students benefitted from the UTA’s growing competence, sharing that the UTA “filled in the gaps that (the lecturers) didn’t mention” and gave “unique perspectives not initially shared by the (lecturers)”. They felt that the UTA provided “a safe environment for people to express their concerns without being judged”.

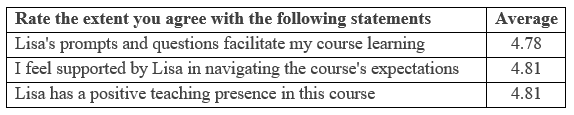

Informal student feedback on UTA at the end of the course on a 5-point Likert Scale (n = 32)

For the UTA, she grew in her appreciation of educators’ role as facilitators, recognising that “effective facilitation requires sharp ground sensing and the ability to frame discussions around students’ existing thoughts, rather than pushing predetermined themes”. She also realised the power of collaboration in education—not just between teachers and students, but among teachers themselves. In particular, navigating the study trip with experienced educators made teaching in unstructured learning environments less intimidating.

.

Conclusion

Integrating UTAs into teaching teams requires a gradual, scaffolded approach that deepens their involvement as they find their footing and assume more complex responsibilities. It requires adaptive collaboration between experienced educators and UTAs, grounded in mentoring, reflective practice, and a shared understanding to navigate the complexities of dynamic learning environments together.

References

Felege, C. J., Hunter, C. J., & Ellis-Felege, S. N. (2022). Personal impacts of the undergraduate teaching assistant experience. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 22(2), 33-66. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v22i2.31306

Hogarth, R. M., Lejarraga, T., & Soyer, E. (2015). The two settings of kind and wicked learning environments. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(5), 379-385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415591878

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Philipp, S. B., Tretter, T. R., & Rich, C. V. (2016). Undergraduate teaching assistant impact on student academic achievement. The Electronic Journal for Research in Science & Mathematics Education, 20(2). https://ejrsme.icrsme.com/article/view/15784