Frances LEE1,*, Alexander LIN2, TAY En Rong, Stephen2, NG Wei Jie, Benedict1, and TAN Wen Cong, Xavier1

1Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music, National University of Singapore (NUS)

2Department of the Built Environment, College of Design and Engineering (CDE), NUS

Sub-Theme

Building Professional Relationships

Keywords

Interdisciplinary, music, built environment, collaborative teaching, higher education

Category

Lightning Talks

How can educators effectively scaffold interdisciplinary education for students of music and built environment? In AY2024/25, five researchers (comprising teaching staff from the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music [YST] and the Department of the Built Environment [DBE], College of Design and Engineering [CDE], at the National University of Singapore) collaborated on a Learning Improvement Project (LIP), supported by a Teaching Enhancement Grant from NUS’s Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology (CTLT), to investigate this question. The aims of the research project were to integrate insights and approaches from built environment into the education of music students, and vice versa, and to guide students in creating performance projects that reflect this integration. Students were given brief lecture-style guidance by mentors from both fields in the first week of collaboration, and were subsequently split into groups to conceive of and execute performance projects, in a mostly self-directed manner but with facilitation and input by the mentors. The resulting end product comprised of performances, given by groups of YST students at various locations within CDE, that showed tangible application of what music students had learnt from their mentors and peers in the field of built environment, particularly applied to spaces that were not purpose-built for musical performances.

One of the key insights gained from the process of executing the project, however, was the educator’s perspective on the opportunities and challenges gained through such a cross-departmental collaboration, in terms of both collegial relationships developed between teaching staff and the sharing of teaching approaches. Through the project, researchers found through self-reflection that navigating interdisciplinary teaching in orthogonal fields has as much to do with negotiating the content being taught as with bridging different outlooks on pedagogy and knowledge acquisition more generally.

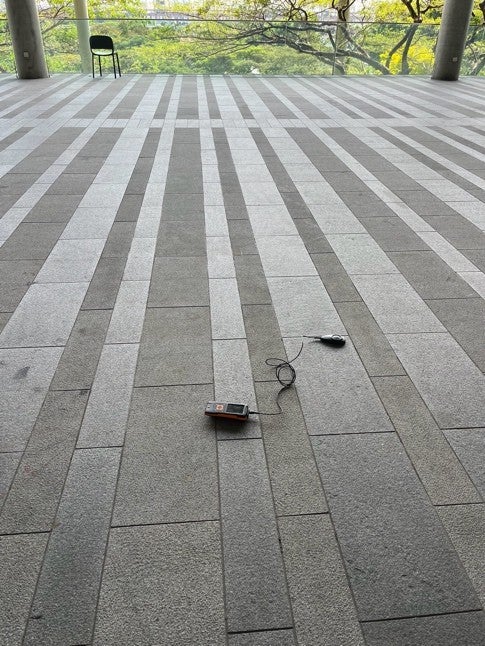

The navigation between objectivity and subjectivity was a core issue that arose in both the disciplinary content and the educators’ approach to assessment. One example was the evaluation of the students’ performance projects, wherein researchers learnt from each other’s different perspectives on defining value and success. The music students’ exploration of objective measurements using scientific instruments (see Figure 1) was paralleled by the YST staff’s encounter with the DBE staff’s quicker turn to considering the quantitative aspects of the assessment model and approach to research within the LIP. The DBE staff and students, on the other hand, were encouraged to embrace the necessary flexibility and multiplicity of perspectives and contexts when faced with artistic productions, to adopt a more audience-focused approach to data collection, and to embrace in-person discussions in the classroom as a way of assessing if learning outcomes had been achieved. Helped in no small part by the collegiality and goodwill that formed the basis of the collaboration between departments, DBE and YST colleagues experienced through this process a growth in awareness of and fluency in ways of thinking and researching that come less naturally to them, which placed them in a position to build even stronger and more efficient interdisciplinary collaborations in the future.

The second core issue faced was the different approaches through which educators sought to bridge the gaps in students’ knowledge and experience. An example was the use of generative AI in building foundational knowledge for music students in the field of built environment and creating a framework to assess potential performance spaces. While all five researchers agreed that encouraging higher-order thinking in students by asking them to create the framework (instead of directly providing one to them directly) was important, the resultant output by the students was inconsistent in its quality, with some students not moving past the broad principles discussed in class to obtain deeper content knowledge and apply it to their use of the performance space. This prompted discussion on how student learning can or should be further scaffolded in the future, and the iterative learning processes that might facilitate this while maintaining student autonomy.

These and other experiences in the project prompted reflection and discussion among the researchers and revisiting of existing literature on interdisciplinary education (e.g., Bossio et al., 2014; de Greef et al., 2017; Ivanitskaya et al., 2002) to explore how interdisciplinary teaching approaches and research might be enhanced in the future, potentially serving as a helpful starting point for navigating collaborations between orthogonal fields in the future.

.

References

Bossio, D., Loch, B., Schier, M., & Mazzolini, A. (2014). A Roadmap for forming successful interdisciplinary education research collaborations: A Reflective approach. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(2), 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.832167

de Greef, L., Post, G., Vink, C., & Wenting, L. (2017). Designing Interdisciplinary Education: A Practical Handbook for University Teachers. Amsterdam University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1sq5t4k

Ivanitskaya, L., Clark, D., Montgomery, G., & Primeau, R. (2002). Interdisciplinary learning: Process and outcomes. Innovative Higher Education, 27(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021105309984