Susan LEE1,*, Corinne ONG Pei Pei2, Amelyn Anne THOMPSON1

Centre for English Language and Communication, National University of Singapore (NUS)

Residential College 4 (RC4), NUS

Sub-Theme

Building Learning Relationships

Keywords

Learning communities, student-educator relationship, perceptions, rapport, boundaries, wellness

Category

Lightning Talks

Introduction

Literature has associated good student-educator relationships (SER) with students’ learning and thriving. Tormey (2021) proposed that students’ perceptions of the emotional quality of SER make a valid dataset for measuring SER. He concluded that students’ perceptions of the teacher’s warmth, trust, and admiration are critical in fostering positive SER. While Tormey proposed a student-centred definition, the educators’ perceptions and wellbeing should be considered too, especially if students looked to them for emotional support.

In addressing the quality of educators’ interactions with students, Hagenauer et al. (2022) recognised that teachers provide support at various levels, from the academic/professional level to the interpersonal/private level. The observation justifies a need to understand what characterises “support” or a “caring relationship” to students at the academic and personal level, and its impacts on both educators and students for care.

To examine the impacts of qualities of a supportive student-educator relationship (SER), this paper distils learning from an NUS learning community (LC) that sought to understand the qualities and practices that characterise SER and its impacts on educators and students. Underlying this purpose was the LC’s interest in discovering the dynamics of student-educator relationships that motivate learning and support teachers’ wellbeing in our classroom. We hoped that this can, in turn, contribute to a body of good practices that higher-education educators across disciplines, can access to advance quality student-educator relationships.

Building our sharing on literature mostly framed in the Euro-American context, the LC considered cultural sensitivities along with the changing profiles of students in the NUS Asian-global demographic blend. We also discussed the experiences of engaging students outside the classroom as interest group advisors and residential fellows, to understand perceptions of engagement in various contexts. The LC identified five major themes and related questions that could elucidate SER, with reference to the extant scholarship and their personal teaching experiences.

Findings

This paper details the findings from the first two meetings:

- Perceptions of care: Reflections on the definitions and perceptions of teachers’ care for students.

- Establishing rapport: How efforts are made to connect with students while maintaining healthy boundaries.

Theme 1 drew on Pranjic (2021)’s recommendations of caring behaviours like sharing of teaching philosophy and opening opportunities to co-create content. LC members shared they perceived care for students as a combination of personal commitment, moral duty, and professional duty. Figure 1 summarises members’ methods of expressing care.

(Source: Authors’ own)

.

Student appreciation of a caring relationship may be observable in students’ actions, such as their initiation of conversations with educators or willingness to participate in classes. Role conflicts, however, could arise, and there is a need for balance between professional boundaries and fairness.

On Theme 2, LC members discussed rapport-building, defined as “an overall feeling between two people encompassing a mutual, trusting, and pro-social bond” (Frisby & Martin, 2010, p. 147), achieved through effective teaching behaviours (Frisby & Munoz, 2021). Our aims included:

- To build trust and facilitate collaboration

- To remove barriers (anxiety) that hamper learning

- To motivate class attendance

- To model openness in creating a safe space, e.g. establishing ground rules.

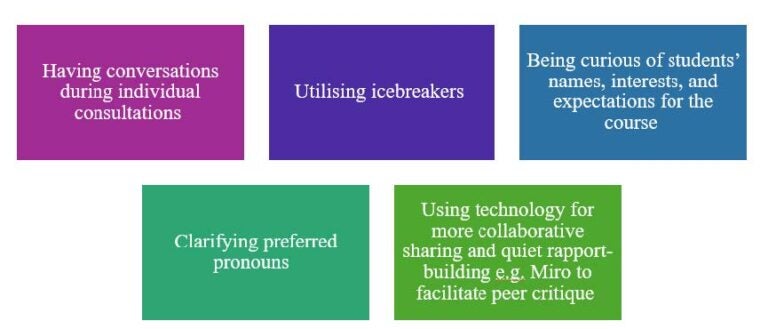

Fig. 2 provides examples of our attempts to build rapport.

(Source: Authors’ own)

.

We also discussed well-intended strategies that could be counterproductive, prompting us to be mindful of student perceptions of bias, extensive discussion of personal matters, and engagement outside class time.

Moving Forward

The LC continues to explore themes on SER, including the impact of care on educators’ wellbeing. After each discussion on literature and practices, members committed to action plans to experiment new practices in specific courses. In time, the LC hopes to share our findings to advance good practices in SER.

References

Frisby, B., & Martin, M. (2010). Instructor-student and student-student rapport in the classroom. Communication Education, 59(2), 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520903564362

Frisby, B., & Munoz, B. (2021). Love me, love my class: instructor perceptions of rapport building with students across cultures. Communication Reports, 34(3), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2021.1931387

Hagenauer, G., & Volet, S. E. (2014). Teacher-student relationship at university: an important yet under-researched field. Oxford Review of Education, 40(3), 370-388. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.921613

Pranjic, S. S. (2021). Development of a caring teacher-student relationship in higher education. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 12(1), 151-163. https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs2021.1.151.163

Tormey, R. (2021). Rethinking teacher-student relationships in higher education: a multidimensional approach. Higher Education, 82, 993-1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00711-w