Arthur LAU Chin Haeng1,* and Manuel Tristan PEREIRA2

1Department of Anatomy, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSOM), National University of Singapore (NUS)

2Faculty of Dentistry, NUS

Sub-Theme

Others

Keywords

Game-based learning, dental education, anatomy education, analog games, non-digital games.

Category

Lightning Talks

Background and Aims

Anatomy education in the dental curriculum can demand high cognitive effort, spatial reasoning and memory retention. At the National University of Singapore Faculty of Dentistry, students are required to learn the human anatomy within their first year. A method of creative teaching and learning is the use of game-based learning which can foster learning outcome with engagement. Game-based learning can be defined as the use of a serious game or an entertainment game in a form of digital or analog to facilitate the achievement of learning outcomes (Whitton, 2012). Such use of games as pedagogical tool is employed in dental education (Sipiyaruk et al., 2018). However, the efficacy of games for learning can depend on their designs. Crucially, the game designs should include co-creation between educators and students to ensure the games meet the requirements of both teaching and learning (Olszewski & Wolbrink, 2017). The aim of this study is to co-designed and developed an analog game for the learning of anatomy for first year dentistry students and determine its efficacy.

Methods

The study is divided into design with development and evaluation phases. During the design and development, the first author (anatomy educator) and second author (dental student) identified the learning outcome to be achieved and the relevant game mechanic to pair with based on the Learning Mechanic-Game Mechanic and Self-Determination Theory (LM-GM-SDT) framework by Proulx et al. (2017). To evaluate the game, a pre-post test was conducted to investigate learning outcome and followed by a qualitative inquiry to explore learning and play experience. Purposive and snowballing sampling method were employed to identify dental students who have completed their first year of dental school. In May 2025, first year dental students from the Faculty of Dentistry were recruited. During evaluation, participants were first brief on how to play the game. This is then followed by a 20–30-minute gameplay and followed by a 30–40-minute focus group discussion. A reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyse the interview transcript, and themes were generated (Braun & Clarke, 201 (NUS IRB: NUS-IRB-2025-31).

Results

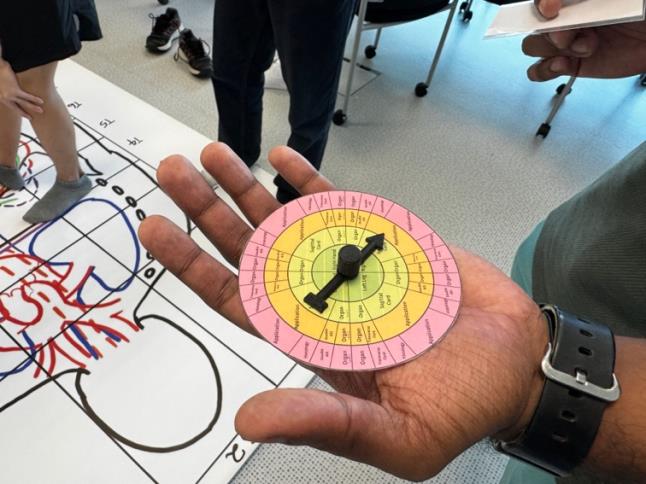

An analog anatomy game was developed using Twister-inspired mechanics because it involves identification and navigation of the correct positioning on a schematic of a human body. The game has four levels which evaluates from the Bloom’s taxonomy level of recall to application, and contains gross human anatomy, sectional anatomy, histology and embryology. Fifteen first-year dental students were recruited. Pre-post-test analysis using Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed a statistically significant improvement in learning outcomes with large effect size (p=0.002, r=0.8). Thematic analysis revealed eight overarching themes. Students valued AnaTwist as a low stake, engaging tool that supported reinforcement, memory, and strategic thinking. However, integration into the formal curriculum, particularly within tutorial settings, was seen as necessary for meaningful use. Design suggestions included deeper question elaboration, debrief sessions, and digital enhancements. Social factors such as timing, peer familiarity, and physical comfort influenced engagement. Assessment alignment and dental-specific content were key motivators for adoption. AnaTwist was ultimately perceived as a supplementary tool that enhanced learning through both cognitive and relational pathways.

Conclusion

AnaTwist demonstrates strong potential as a low-stakes, high-engagement analog game that supports anatomy learning through physical interaction, recall, and reflection. For such innovations to be adopted meaningfully, they must align with the curriculum, be well-facilitated, and show clear relevance to learning goals and assessments. This study provides evidence to inform the deliberate design and integration of analog games in health sciences education, especially where digital access may be limited.

Figures

.

.

.

.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). Thematic Analysis. In T. Teo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology (pp. 1947-1952). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614- 5583-7_311

Olszewski, A. E., & Wolbrink, T. A. (2017). Serious gaming in medical education: A proposed structured framework for game development [Article]. Simulation in Healthcare, 12(4), 240-253. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000212

Proulx, J.-N., Romero, M., & Arnab, S. (2017). Learning mechanics and game mechanics under the perspective of self-determination theory to foster motivation in digital game-based learning. Simulation & Gaming, 48(1), 81-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116674399

Sipiyaruk, K., Gallagher, J. E., Hatzipanagos, S., & Reynolds, P. A. (2018). A rapid review of serious games: From healthcare education to dental education [Article]. European Journal of Dental Education, 22(4), 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12338

Whitton, N. (2012). Games-Based Learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (pp. 1337-1340). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_437