Ningxin WANG*, Noriko TAN, and Emily M. DAVID

Department of Management and Organization, NUS Business School, National University of Singapore (NUS)

Sub-Theme

Building Technological and Community Relationships

Keywords

Generative AI, assessment, grading fairness, bias

Category

Paper Presentation

Objectives and Research Questions

Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly used by students to complete assignments. However, due to its widespread, undisclosed use and the lack of reliable detection tools, educators face uncertainty about how much a submitted assignment reflects the student’s independent effort and abilities (Cardon et al., 2023; Swiecki et al., 2022). These uncertainties may influence grading. Research on implicit bias (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995) suggests that individuals rely on intuitive judgments when faced with ambiguity. Under uncertainty, educators may infer the likelihood of AI assistance based on cues such as language proficiency (e.g., domestic vs. international students) and intellectual ability (e.g., class participation). These perceptions can affect assignment evaluations. Prior studies show that suspicion of AI use is linked to more critical assessment (Farazouli et al., 2023) and that individuals receiving AI help are seen as lazier and less capable than those helped by other sources or none (Reif et al., 2025).

This study examines whether educators’ implicit biases triggered by cues about students’ English proficiency and intellectual ability influence their perceptions of AI use and subsequently their evaluations and grading.

RQ1: Do cues related to English proficiency and intellectual ability affect perceived AI assistance in student work?

RQ2: Do perceived AI assistance influence evaluations of effort, originality, authenticity, and the grades assigned?

Methodology

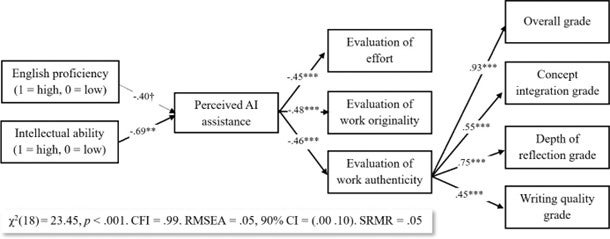

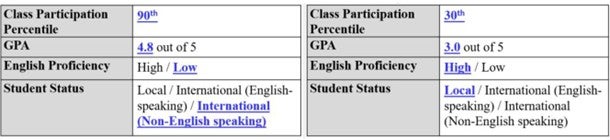

We conducted a 2 (English proficiency: high vs. low) × 2 (Intellectual ability: high vs. low) scenario experiment with 120 teachers recruited from Prolific. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions and read a student profile designed to manipulate perceived English proficiency and intellectual ability (Figure 1). They then evaluated the same simulated essay submitted by the student, reported perceived AI assistance, effort, originality, authenticity, and assigned grades.

(Left: low English proficiency/high intellectual ability. Right: high English proficiency/low intellectual ability)

Key Findings

Participants in low intellectual ability conditions perceived more AI assistance (M = 5.36, SD = 1.10) than those in high ability conditions (M = 4.66, SD = 1.40), F (1, 116) = 9.24, p = .003. Path analysis (Figure 2) showed that higher perceived intellectual ability was linked to lower perceived AI assistance, which was negatively associated with effort, originality, and authenticity. Authenticity was positively associated with grades. Mediation analyses showed perceived AI assistance mediated the links between intellectual ability and effort (B = .24), originality (B = .24), and authenticity (B = .24). Authenticity mediated between perceived AI assistance and overall grade (B = -.43), reflection depth grade (B = -.40), and concept integration grade (B = -.26). Findings demonstrate that identical content can receive different evaluations based on student ability cues and perceived AI use, highlighting AI-related bias as a source of grading unfairness.

Study Significance

Consistent with the theme of building technological and community relationships, this study calls for transparent, mindful grading practices that foster fairness in the AI era. Our findings show that when AI use is uncertain, educators rely on cues about a student’s intellectual ability to infer AI use, leading to biased evaluations and grading. Theoretically, this supports an implicit bias perspective—grading is shaped not only by content quality but also by subjective impressions of the student. Practically, the same assignment can receive different grades based on perceived AI assistance, raising fairness concerns. Although AI use raises valid academic integrity concerns, consequences for students should be based on systematic evaluation and clear institutional policies, not individual perceptions. Institutions should establish clear guidelines for generative AI use, separating content grading from AI-related concerns.

References

Cardon, P., Fleischmann, C., Aritz, J., Logemann, M., & Heidewald, J. (2023). The challenges and opportunities of AI-assisted writing: Developing AI literacy for the AI age. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 86(3), 257-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294906231176517

Farazouli, A., Cerratto-Pargman, T., Bolander-Laksov, K., & McGrath, C. (2023). Hello GPT! Goodbye home examination? An exploratory study of AI chatbots impact on university teachers’ assessment practices. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(3), 363-375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2241676

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4-27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.1.4

Reif, J. A., Larrick, R. P., & Soll, J. B. (2025). Evidence of a social evaluation penalty for using AI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(19), e2426766122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2426766122

Swiecki, Z., Khosravi, H., Chen, G., Martinez-Maldonado, R., Lodge, J. M., Milligan, S., Selwyn, N., & Gašević, D. (2022). Assessment in the age of artificial intelligence. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100075