LIU Mei Hui1,2,*, and Mark GAN Joo Seng1

1Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Technology (CTLT), National University of Singapore (NUS)

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Science (FoS), NUS)

Sub-Theme

Building Learning Relationships

Keywords

Peer feedback, large classes, evaluative judgement, iterative learning

Category

Paper Presentation

Introduction

Feedback is a cornerstone of effective student learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). However, delivering meaningful feedback in large classes presents significant challenges, including limited instructor capacity, delays, and a tendency toward one-way information transmission that often leaves students and teachers dissatisfied. These constraints can undermine the development of evaluative judgement and self-regulation skills, which are essential for academic growth. Carless (2015) proposed a new feedback paradigm where more focus is placed on interaction, student sense-making, and outputs in terms of future student action. The feedback format shifts from a one-way transmission to a social constructivist approach where students are enabled to engage with and use feedback to facilitate their own learning (Winstone & Carless, 2020).

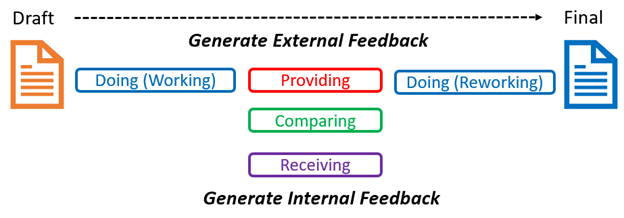

Peer feedback is also a complex, multi-step process where both internal (self-generated) and external (peer-provided) feedback can be harnessed for deeper learning. This also positions students as active agents in the feedback process (Carless & Boud, 2018).

To allow students in large classes to benefit from peer feedback, an essay assignment was redesigned to incorporate peer feedback within a draft-final process. This study addresses two questions: (1) What are students’ perceptions of peer feedback received? (2) How does participation in peer feedback influence students in their own essays?

Methodology

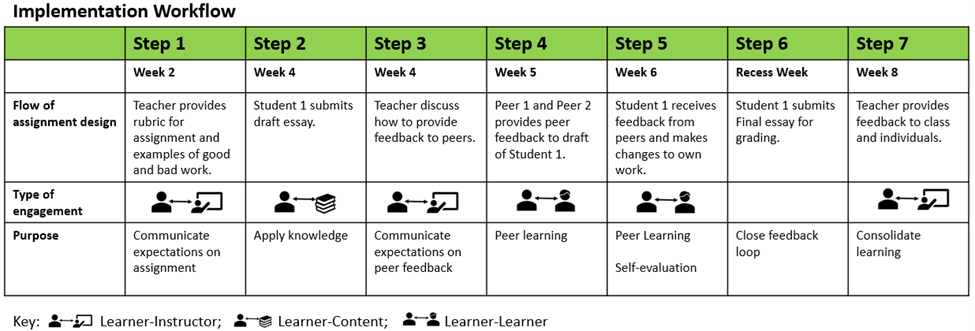

To investigate these questions within the context of a large undergraduate Nutrition course, we implemented a draft–rework essay assignment which included peer feedback (Figure 1).

Students were randomly assigned to anonymous groups of three, each submitting an initial draft of a written assignment. Drafts were then exchanged within each group, requiring students to provide feedback to two peers and, in turn, receive feedback from two others. After considering peer and internal feedback, students revised and resubmitted their assignments, with final versions assessed by teaching assistants. Five cohorts of students (n=421) were surveyed for their perceptions of peer feedback received, and we examined how students improved their work from draft to final.

Results

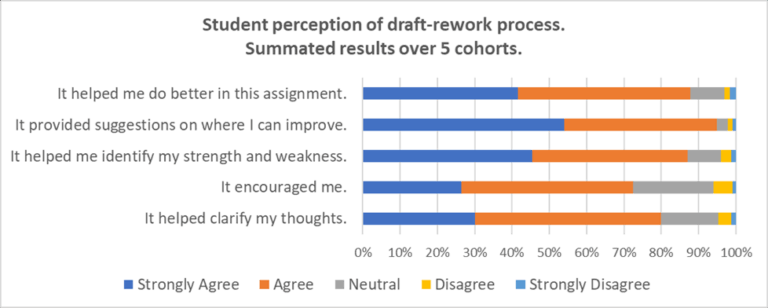

Qualitative data were gathered through student surveys, capturing perceptions of learning benefits associated with giving and receiving feedback (Figure 2). The survey result suggests that peer feedback was helpful and provided suggestions on where students can be improved while identifying strengths and weaknesses. Most, although not all, felt supported in their learning by their peers.

Students’ qualitative comments suggest that participating in peer feedback also enhanced their learning experience beyond receiving feedback. In several instances, students learned from reading other peers’ work to improve their own quality of work (Table 1, underlined). This aligns with our quantitative data, where students found that participating in peer feedback clarified their own thoughts. This suggests the process expanded students’ capacity for reflection and self-assessment.

Representative qualitative comments from students

| Representative comments of students perceived the benefits of the assignment |

This learning experience was very unique as I got to see the different ways each of us chose to approach this assignment, and helped me to better understand the pros and cons of each of the different ways. I was then able to have a better idea of how i wanted to present my information, and incorporated some of the methods my peers have used or suggested to me in my own writing. |

| Without reading my peers’ works and feedback, I don’t think I would have known how to improve my draft even though I was pretty dissatisfied with my own writing. Also, it made me feel slightly fulfilled knowing that I could also help my peers just like how they helped me. I think everyone has something to learn from each other and it was a meaningful experience overall for me. |

The peer feedback session was really helpful as it allowed us to learn a lot from each other’s writing and suggestions, to discover details that we had missed, to feel the spark of thought, and to have the opportunity to enhance ourselves before the final submission. It was a brilliant learning experience to me. |

The results demonstrate that integrating a draft–rework design with peer feedback in large classes yields improvements in student learning outcomes. Students reported that both providing and receiving feedback, along with opportunities for self-regulation and co-regulation, contributed to their development of evaluative judgement and a deeper understanding of assignment criteria.

Conclusion and Significance

The significance of this study lies in its demonstration that embedding multi-component, iterative peer feedback processes into large-class curricula can overcome traditional feedback limitations, enhancing students’ evaluative judgement and self-regulation skills. By interweaving opportunities for both internal and external feedback (Figure 3), this approach moves beyond feedback as a unidirectional transmission, fostering a more interactive and impactful learning environment.

The findings underscore the need for educators to reconceptualise peer feedback as an integrated, formative process (Nicol, 2014), providing students with multiple opportunities to compare, reflect, and act on feedback throughout the learning cycle, an imperative for scalable, high-quality feedback in large classes. The findings have limitations as it remains unclear if similar benefits apply to other assignment types, like group work. Uneven group contributions, not examined here, may affect individual learning and perceived benefits. Future research should address this to optimize feedback strategies.

References

Carless, D. (2015). Exploring learning-oriented assessment processes. Higher Education, 69(6), 963–976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9816-z

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., & Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: A peer review perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(1), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.795518

Winstone, N., & Carless, D. (2020). Designing effective feedback processes in higher education: A learning-focused approach. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351115940