Judice L. Y. KOH1, and Kenneth BAN1,2

1Department of Biomedical Informatics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSOM), National University of Singapore (NUS)

2Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science (FoS), NUS

Sub-Theme

Building Learning Relationships

Keywords

Digital-health literacy; inter-professional education; social network analysis

Category

Paper Presentation

Introduction

Digital transformation is reshaping healthcare practice, yet graduates from healthcare professional programmes may not be “digitally ready”, thus creating a curricular blind spot whereby graduates may master Pharmacology or Anatomy but struggle to interrogate specialised healthcare data, safeguard patient information or critically appraise a telemedicine app or medical chatbot. BMI1101A/C “Digital Literacy for Healthcare” is an inter-professional common-curriculum course that introduces second-year students from the Departments of Medicine, Pharmacy, Nursing and Dentistry at NUS to core topics in Digital Healthcare. Managing large-cohort inter-professional education, simultaneously overlaid with digital literacy skills which is largely new to the students, and coupled with an overarching goal of fostering inter-disciplinary relationships, posed a complex, multi-facet challenge (Shuyi et al., 2024; Zainal et al., 2022; Poncette et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2018).

The BMI1101A/C syllabus spirals over 10 weeks (Table 1). Students begin with the foundations of digitalisation, then master targeted literature searches using PubMed-MeSH and Perplexity AI. Subsequent lessons introduce Electronic Health Records (EHR) workflows, telemedicine, and patient apps. After mid-semester, the focus shifts into computational concepts, including computational thinking to AI/Machine Learning and prompt engineering for healthcare inquiries. In its inaugural run, the delivery was hybrid, with a combination of online tutorial sessions synchronously conducted by eight tutors via Zoom, and on-site sessions convening ~350 students into two lecture theatres where the lead tutors facilitated tutorial activities with support from tutors circulating to assist the students.

Course roadmap and learning objectives

| Week(s) | Topic | Key Learning Objectives |

| 1 | Digital Identity & Safety | Explain digital footprints and data-privacy; model safe professional conduct online. |

| 2 | Digital Searching & Appraisal | Construct MeSH/PubMed strategies; critique bias and credibility. |

| 3-4 | Healthcare Informatics & EHR | Describe EHR data flows; identify governance and data-quality issues. |

| 5 | Telemedicine & Patient Apps | Apply regulatory frameworks; evaluate privacy and clinical safety. |

| 6 | Computational Thinking | Use decomposition, pattern recognition and simple algorithms to automate tasks. |

| 7-10 | Introduction to AI/ML & Generative AI | Differentiate ML paradigms; interpret model outputs; debate AI ethics and workflow fit. |

.

This study draws insights from student learning peer-evaluated communities of ~700 students who participated in the inaugural run using network-based analysis—an approach which was used in previous studies to link student engagement patterns to academic outcomes (Williams et al., 2019; Vignery & Laurier, 2020). Combining the network findings with the student feedback, we examine the course’s relational pedagogy, propose refinements to the framework, and highlight potential pitfalls.

Methodology

Relational Pedagogy

A spectrum of learning relationships

The syllabus blends healthcare with computational themes, and is intrinsically interdisciplinary. Most tutors joined with medical or computational backgrounds, and were cross-trained through weekly alignment briefings, thereby expanding the spectrum of learning relationships underpinning the course (Table 2). Moreover, online and onsite tutorial sessions present different modalities of the relational pedagogy (Figure 1). Lead tutors are domain experts who designed and developed the weekly learning materials comprising pre-reading videos, hands-on tutorial activities, and a “tutor toolkit” with model answers, audio clips and lecture scripts. During online tutorials, each tutor guided four project groups (PGs) of ~40 students, steering discussions and problem-solving activities. By contrast, onsite tutorials were fronted by lead tutors; tutors circulate through the lecture theatres, providing specialist intervention to students during practical tasks.

The physical format facilitated knowledge diffusion through direct delivery of materials, and students interacted within a denser peer network. However, the tutor-student relationship changed correspondingly, from a facilitator role to roaming coaches of student groups, and lead tutors shouldering a heavier cognitive load. In such a scenario, quieter students become unnoticed unless tutors deliberately seek them out.

Learning relationships underpinning the course

Relationship | Scope | Ratio (Upper bound) |

Tutor – Project Group (TPG) | Each tutor facilitates discussion and hands-on tasks for four project groups during weekly tutorials. | 1 tutor: 40 students (4 PGs) |

Lead Tutor-Project Group (LTPG) | Lead tutor delivers instructions and models activities in onsite tutorial sessions. | 1 lead tutor: 160 students (16 PGs) |

Inter-Project Group (IPG) | Peer-to-peer exchanges among project groups | 40 students (online) or 160 students (onsite) |

Lead Tutor – Tutor (LTT) | Lead tutors prepare weekly “tutor toolkit”, and conduct weekly alignment briefings | 1 lead tutor : 16 tutors |

.

Interprofessional Learning Communities

At semester’s end, each project group presented a formal evaluation or prototype related to digital healthcare. Students then carried out confidential peer evaluation using TEAMMATES (https://teammatesv4.appspot.com), rating their group members on four behaviour themes—participation, cooperation, timeliness and technical contribution (Cook et al., 2017). The resulting scores ranged from 1 to 5, with an average of 4.3.

Discussion

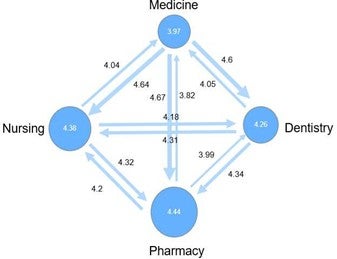

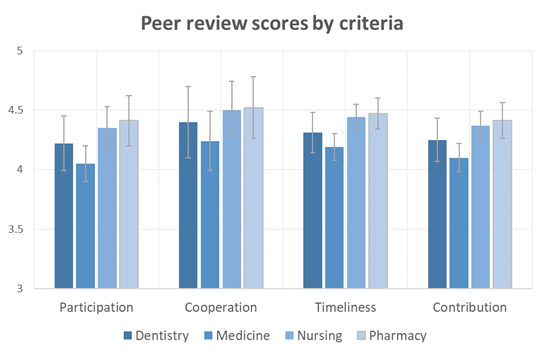

Analysis of the peer-review network reveals asymmetry between Givers and Receivers across the four faculties. Pharmacy students received the highest average peer review score (4.44), while Medicine students received the lowest (3.97) (Figure 2). This observation is consistent across the four themes, with participation and contribution emerging as the weakest area, thus suggesting disparities in engagement and workload distribution among the faculties (Figure 3).

.

.

.

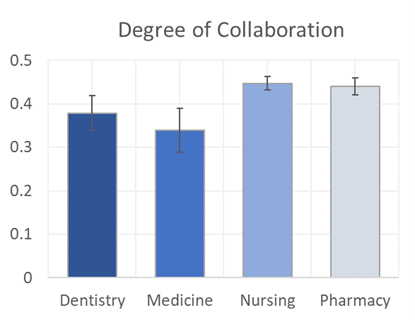

Using the peer-reviewed “level of cooperation” scores, we computed each student’s weighted local clustering coefficient as a proxy for their degree of collaboration. The results show that Nursing and Pharmacy students exhibit stronger interconnections with their peers, suggesting higher levels of collaborative engagement. In contrast, Medicine students exhibit sparser network ties, which may be attributed to scheduling frictions and heavier academic demands (Figure 4).

In summary, this study examines the spectrum of learning relationships underpinning an interprofessional, large-cohort digital literacy course for undergraduates. Through network analysis, we also did a deep dive into the collaborative relationships among students and uncovered discrepancies in expectations and participation across the four faculties. By monitoring and recalibrating these relational structures, we aim to strengthen the inter-professional synergy in future offerings of the course.

References

Cook, A. R., Hartman, M., Luo, N., Sng, J., Fong, N. P., Lim, W. Y., … & Koh, G. C. H. (2017). Using peer review to distribute group work marks equitably between medical students. BMC Medical Education, 17, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0987-z

Poncette, A. S., Glauert, D. L., Mosch, L., Braune, K., Balzer, F., & Back, D. A. (2020). Undergraduate medical competencies in digital health and curricular module development: mixed methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(10), e22161. https://doi.org/10.2196/22161

Reid, A.‑M., Fielden, S. A., Holt, J., MacLean, J., & Quinton, N. D. (2018). Learning from interprofessional education: A cautionary tale. Nurse Education Today, 69, 128‑133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.07.004

Shuyi, A. T., Zikki, L. Y. T., Mei Qi, A., & Koh Siew Lin, S. (2024). Effectiveness of interprofessional education for medical and nursing professionals and students on interprofessional educational outcomes: A systematic review. Nurse Education in Practice, 74, 103864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103864

Vignery, K., & Laurier, W. (2020). Achievement in student peer networks: A study of the selection process, peer effects and student centrality. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101499

Williams, E. A., Zwolak, J. P., Dou, R., & Brewe, E. (2019). Linking engagement and performance: The social network analysis perspective. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 15(2), 020150. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.15.020150

Zainal, H., Xin, X., Thumboo, J., & Fong, K. Y. (2022). Medical school curriculum in the digital age: perspectives of clinical educators and teachers. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 428. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03454-z